More than 20 million Americans are covered by state and local government pensions. Unlike the 401(k) plans found in the private sector, these “defined benefit” plans promise to pay retirees a set amount of money every month for the rest of their lives.

Most people who work for the government depend on these generous programs to keep their finances in order. For many, they’re one of the main reasons they want to work for the government. Yet the plans, by their own reckoning, are underfunded to the tune of $1. 6 trillion.

That shortfall would leave them 75 percent funded, which may not sound too dire. But Joshua Rauh, a finance professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business and head of the Hoover Institution’s State and Local Governance Initiative, says that number doesn’t even come close to describing the problem.

Rauh, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), thinks that the real amount of unfunded pension liabilities is around $5. This is the difference between the benefits that are promised and the assets that are set aside to pay for them. 1 trillion, which translates to an overall funding ratio of less than 50 percent.

Rauh and Oliver Giesecke, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, gathered data on the pensions in every state, as well as the 170 biggest cities and 100 biggest counties in the U.S. Their sample covers 90 percent of public pension funds by assets from 2014 to 2022.

The problem, as they explain in a recent paper, is that future pension obligations are being grossly undervalued — and the discrepancies are adding up. Over the nine-year span of their study, unfunded liabilities grew by 50 percent, even as stocks surged and state and local budgets contributed more to pension plans. Meanwhile, to generate more revenue, fund managers chased higher returns by investing in riskier assets like real estate, private equity, and hedge funds.

That combination of a huge funding gap and growing risk exposure should raise alarms about the long-term viability of these plans, Rauh says. “The current system is not sustainable, and state and local governments are not being candid with their employees or taxpayers about it.”

“When a state government promises to pay its workers a pension after they retire, it’s essentially incurring a debt on which future payments must be made,” Rauh explains. States set aside money from their budgets each year to pay those benefits.

Of course, that money doesn’t sit idle; annual contributions to the pension fund are invested in financial assets. Assuming those assets will appreciate over time, that means current contributions can be less than the dollar amount of the future promise. But how much less?

To determine that, administrators discount the future sum by a percentage reflecting the rate of return they expect to earn on that money in the meantime. The higher the discount rate, the smaller the present value of the liability on the books, and the less they need to sock away.

As you might expect, cash-strapped states and municipalities are inclined to optimism. In 2022, the average discount rate used by funds was 6.7 percent. That choice was based on recent investment results, but it reflected yields on risky assets during a market boom — which are anything but certain over the long term. (The actual return on fund assets that year was negative 3.2 percent.)

Pension obligations, on the other hand, are effectively ironclad commitments — often guaranteed by law and almost certainly by political considerations. “It’s a total mismatch,” Rauh says. “You have risky assets backing up risk-free liabilities.”

The current system ignores that disconnect. “Those high-targeted returns may or may not be achieved in any year, but public sector accounting and budgeting proceed under the assumption that they will be achieved with certainty,” Rauh says.

To be sure of having enough money to pay retirees, funds would have to stick to risk-free securities like U.S. Treasury bonds, which averaged just 2.1 percent over the past decade. That doesn’t mean they should, he says. (They’d be worse off if they’d missed the recent stock market boom.)

But that low, default-free 2.1 percent rate is the one that markets would use to measure the true value of future pension obligations, say Rauh and Giesecke. Doing so greatly increases the present value of existing pension promises and increases total unfunded liabilities from $1.6 trillion to $5.1 trillion.

The resulting market-value funding ratios vary widely among plans. In 2022, Wisconsin’s plan was 74 percent funded; New York’s was nearly 65 percent funded. At the other end of the list, New Jersey’s plan was just 29 percent funded. The nation’s biggest public pension fund, California’s CalPERS, had a market-value funding ratio of around 48 percent — significantly below the 77 percent it reported. (Rauh and Giesecke’s data on state and local pension plans are available on this dashboard.)

“The method used by public pension systems makes no sense,” Rauh says. “It’s just basic finance: The present value of a stream of payments is determined by the risk properties of those payments. It has nothing to do with the assets used to back them.”

Have you ever wondered what happens when companies promise retirement benefits they might not be able to fulfill? That’s where pension obligation risk enters the picture and it’s a bigger deal than most people realize.

I’ve been researching financial risks for years, and pension obligation risk continues to be one of those complex topics that affects both businesses and employees alike. Today, we’re gonna break it down into understandable chunks so you can grasp what it means for companies, investors, and even you as a potential pension recipient.

What Is Pension Obligation Risk?

A company faces pension obligation risk when its contractual obligations to a pension scheme could cause it to lose money. According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), this risk happens when a company’s pension liabilities might be higher than its assets that can cover those liabilities.

In simple terms, it’s the chance that a business won’t be able to pay its workers the retirement benefits it promised.

From an investor’s point of view, pension risk is the chance that a defined-benefit pension plan that isn’t funded properly will hurt a company’s earnings per share (EPS) and overall financial health.

It’s important to note that pension obligation risk only exists with defined-benefit plans, not defined-contribution plans. Here’s why:

- Defined-benefit plans promise specific, predetermined payments to retired employees. The company bears the investment risk because it must ensure it has enough funds to pay these guaranteed benefits.

- Defined-contribution plans (like 401(k)s) place the investment risk on employees. The company only commits to contributing a certain amount to employee retirement accounts, not to providing specific benefit amounts.

The Financial Impact of Pension Obligation Risk

When a pension plan becomes underfunded (meaning its assets are less than its liabilities), it can trigger serious financial consequences for the company:

-

Required Cash Contributions: If a pension’s assets fall below certain funding thresholds (typically 80-95%), the employer must increase its contributions to the pension portfolio, usually in cash.

-

Less Equity and Earnings: These extra cash payments can make a company’s equity and earnings per share much lower.

-

Potential Loan Defaults: A decrease in equity might trigger defaults under corporate loan agreements, leading to increased interest rates or even bankruptcy in extreme cases.

-

Balance Sheet Volatility: Pension obligations can cause significant fluctuations in a company’s financial statements due to changes in interest rates and investment returns.

For investors, these risks make it crucial to evaluate the funding status of a company’s pension plan before investing. However, limited disclosure and sometimes murky accounting practices can make this assessment challenging.

Types of Risks Within Pension Obligations

Pension obligation risk encompasses several specific risk types:

1. Longevity Risk

This is the risk that pension plan participants will live longer than expected, resulting in higher-than-anticipated payouts. When retirees live longer, companies must pay benefits for extended periods, increasing the total liability.

2. Investment Risk

The risk that funds set aside for paying retirement benefits fail to achieve expected investment returns. Poor investment performance can significantly increase the gap between pension assets and liabilities.

3. Interest Rate Risk

Changes in the interest rate environment can cause unpredictable fluctuations in balance sheet obligations and required contributions. When interest rates fall, pension liabilities increase because the present value of future obligations grows.

4. Proportionality Risk

This occurs when a company’s pension liabilities become disproportionately large relative to its remaining assets and liabilities. Such imbalance can threaten the overall financial stability of the organization.

How Companies Address Pension Obligation Risk

Organizations employ various strategies to manage pension obligation risk:

Pension Risk Transfer (PRT)

One popular approach is Pension Risk Transfer, where a company transfers the financial responsibility and administrative burden of a defined-benefit pension plan to a life insurance company. There are several methods for this:

-

Longevity Reinsurance: Transferring just the longevity risk to a reinsurer.

-

Buy-in: The insurer pays the monthly annuity amount to the pension plan, while the plan continues making payments to participants.

-

Buy-out: The insurer takes direct responsibility for making specified annuity payments to each covered participant.

-

Lump-Sum Payments: Offering vested plan participants a one-time payment to voluntarily leave the plan early.

These transfers can help companies avoid earnings volatility and focus on their core businesses instead of pension management.

Pension Obligation Bonds (POBs)

Some state and local governments issue Pension Obligation Bonds (POBs) as part of their strategy to fund unfunded pension liabilities. These are taxable bonds issued with the assumption that the proceeds, when invested with pension assets in higher-yielding classes, will achieve returns greater than the interest rate owed on the bonds.

However, the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) advises against issuing POBs for several reasons:

- The invested POB proceeds might fail to earn more than the interest rate owed, increasing overall liabilities.

- POBs are complex instruments carrying considerable risk, sometimes incorporating derivatives or swaps.

- Issuing taxable debt to fund pension liability increases the jurisdiction’s bonded debt burden.

- POBs are often structured to defer principal payments, potentially increasing overall costs.

- Rating agencies may not view POB issuance positively unless it’s part of a comprehensive plan to address pension funding issues.

Evaluating Pension Obligation Risk as an Investor

If you’re an investor looking at companies with defined-benefit pension plans, here are some factors to consider:

1. Funding Status

Determine how fully the company’s pension liability is funded. “Underfunded” means the assets (investment portfolio) are less than the liabilities (obligations to pay pensions).

2. Contribution Composition

Check what the pension fund consists of. Under IRS rules, pensions may be funded by cash contributions and company stock (with limitations). Companies often contribute as much of their own stock as allowed to reduce cash contributions, but this creates poor portfolio diversification.

3. Financial Health Assessment

Analyze the company’s overall financial condition and its ability to make additional contributions if needed.

4. Disclosure Quality

Evaluate how transparent the company is about its pension obligations and assumptions.

Real-World Implications of Pension Obligation Risk

In recent years, we’ve seen the consequences of pension obligation risk play out in several scenarios:

- Local jurisdictions across the country have faced increased financial stress due to their reliance on Pension Obligation Bonds.

- Some companies have seen significant impacts on their earnings and stock prices due to unexpected pension contributions.

- Union-heavy industries often face higher pension risks due to their stronger defined-benefit pension traditions.

The Bottom Line: Why This Matters to You

Even if you’re not directly involved in corporate finance or investment, pension obligation risk might affect you in several ways:

- As an employee: If you’re counting on a defined-benefit pension for retirement, the financial health of your employer’s pension plan directly impacts your future security.

- As an investor: Understanding pension obligation risk helps you make more informed investment decisions by recognizing potential hidden liabilities.

- As a taxpayer: For public sector pensions, funding shortfalls might eventually lead to higher taxes or reduced services.

The way companies and governments manage pension obligation risk will continue to evolve as demographics shift and financial markets fluctuate. By understanding these risks now, you’ll be better equipped to navigate the changing landscape of retirement planning and investment.

For me, the biggest takeaway is that pension obligation risk isn’t just a corporate finance issue—it’s a societal challenge that affects workers, investors, and communities alike. As we move forward, transparent accounting, prudent risk management, and realistic benefit promises will be essential to addressing this complex financial challenge.

Additional Resources

If you’re interested in learning more about pension obligation risk, check out these resources:

- NAIC Pension Risk Transfer Page

- Investopedia’s articles on pension risk

- MetLife Pension Risk Transfer Poll

- American Academy of Actuaries’ Pension Risk Transfer Issue Brief

Have you ever dealt with pension concerns in your own financial planning? I’d love to hear your experiences in the comments below!

Betting on bull markets

Pension sponsors say none of this will matter if their asset portfolios hit their targets — as they often have. “And if not?” Rauh asks. “I don’t think people realize their governments are gambling on endless bull markets, and those bets are being underwritten by taxpayers. ”.

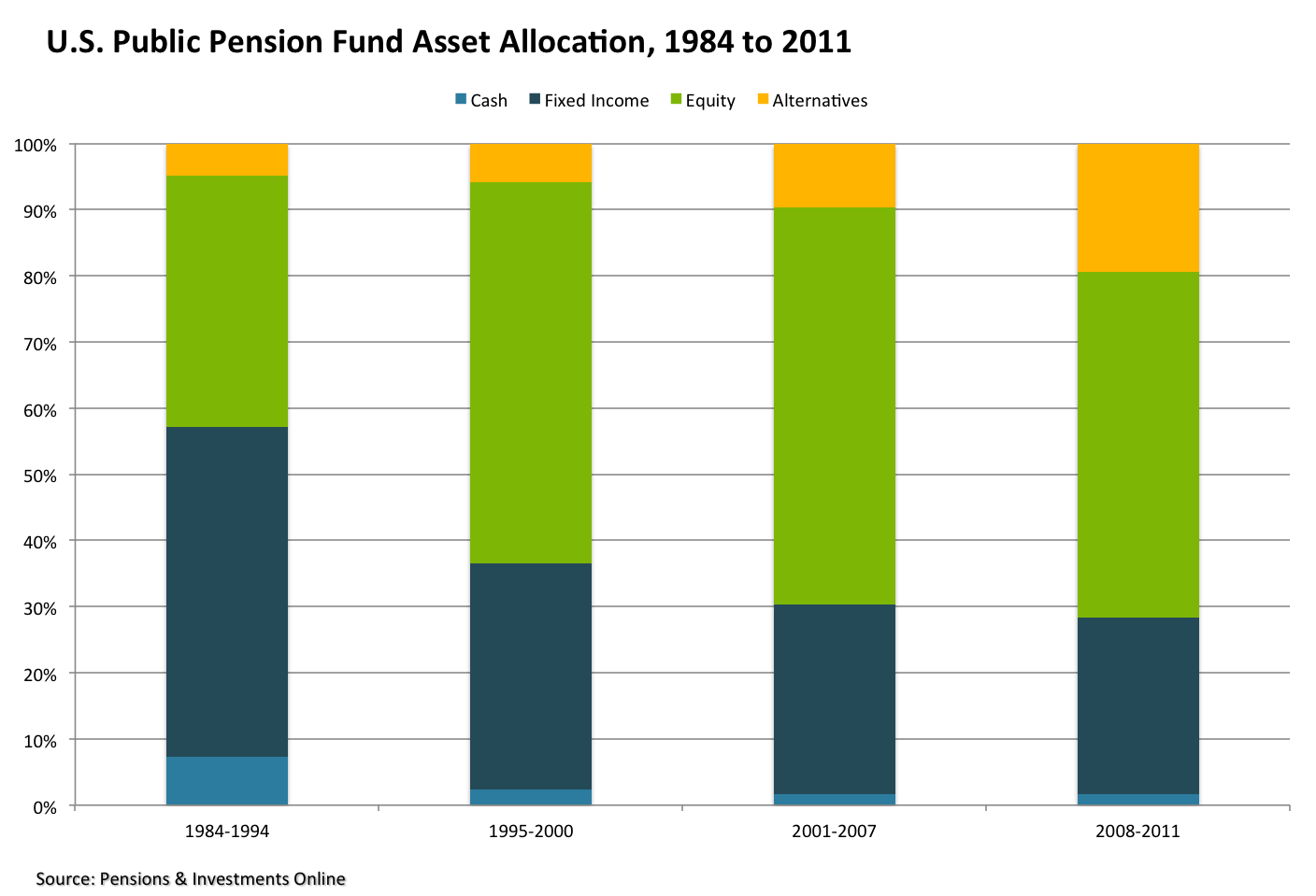

The data shows that public pensions have increased their risk exposure over the past 30 years, investing not just in publicly traded stocks but also more speculative assets like private equity. And those with lower funding ratios, in particular, were more aggressive in their investments.

That’s partly an effort to make up ground. But it also results from a perverse incentive in the current system, Rauh says. More risk means higher expected returns. And since funds use target returns to discount their liabilities, that higher discount rate makes their balance sheet look healthier, even if the assets underperform.

This accounting creates a false picture of the cost of public employment, Rauh says. “You pay your employees a salary, but every year you also have to pay more for their pensions, which is basically deferred pay.” Aggressive discounting makes that deferred amount look smaller. ” It also gives the impression that governments are contributing enough to pension funds. That’s pretty remarkable, considering that annual pension contributions as a percentage of government payroll have increased from 22 percent to 28 percent in the past decade.

With proper discounting, even those contributions fall short of the true cost in every single state, the researchers found. “They should really be putting in a lot more—around 40 percent of payroll—to keep these plans going,” Rauh says.

Financial Q&A: How do pension risk transfers work?

FAQ

What is the pension obligation risk?

Pension obligation risk is defined in GENPRU 1. 2. 31R(5) as the ‘risk to a firm caused by its contractual or other liabilities to or with respect to a pension scheme (whether established for its employees or those of a related company or otherwise)’.

What is a pension obligation?

Pension obligations refer to the financial commitments an employer has to its current and former employees for their retirement benefits. These obligations represent the present value of future pension payments that the employer is legally or contractually required to make to its employees upon retirement.

What is a pension risk?

A defined-benefit (DB) pension provider wants to get out of some or all of its duties to give plan participants a guaranteed income in retirement. This is called pension risk transfer.

What are three ways you could lose your pension?

Economic downturns, company bankruptcies, plan terminations, and even personal circumstances like divorce settlements can impact what you ultimately receive.

What are defined pension obligations?

Defined pension obligations are a huge debt for businesses that promised their current and former workers a steady income in retirement. The pension provider may alternatively seek to transfer some risk to insurance companies via annuity contracts or through negotiations with unions to restructure the terms of the pension.

What is pension risk transfer?

A defined-benefit (DB) pension provider wants to get out of some or all of its duties to give plan participants a guaranteed income in retirement. This is called pension risk transfer. Defined pension obligations represent an enormous liability to companies that have guaranteed retirement income to its current and past employees.

What is a Pension Risk Transfer (PRT)?

A pension risk transfer (PRT) is a transaction in which a company with a defined benefit pension plan (i.e., a retirement plan that generally o ers a specified monthly benefit in retirement) seeks to settle some (or all) of its future financial obligations to pay retirement benefits.

Why do companies transfer pension risk?

Companies transfer pension risk to avoid earnings volatility and enable themselves to concentrate on their core businesses. The total annual cost of a pension plan can be hard to predict due to variables in investment returns, interest rates, and the longevity of participants.

What happens when a defined benefit pension obligation is transferred?

When a defined benefit pension obligation is transferred to a group annuity, the safeguards and consumer protections for a ected individuals shift from the federal pension regulatory system to the state insurance regulatory system.

What is a defined benefit pension plan?

A transaction in which a company with a defined benefit pension plan seeks to settle some (or all) of the plan’s future financial obligations to pay retirement benefits by pre-paying those costs. The company (also called the plan sponsor) pays a single premium to an insurance company in