Hey there, fellow investors! If you’re dipping your toes into the stock market or are already swimming in trades, you’ve probably wondered about the tax consequences of all those clicks to buy and sell It’s a question I get all the time from readers “Do you pay taxes on every stock trade?” The short answer is no—but as with most tax matters, there’s more to the story than a simple yes or no

Today, I’m breaking down exactly when stock trades trigger taxes, how much you might owe, and some smart strategies to potentially reduce your investment tax bill. Let’s dive in!

The Basics: When Stock Trades Become Taxable Events

First things first: not every stock transaction creates an immediate tax bill. Here’s what actually gets taxed:

Taxable Stock Events:

- Selling stocks for a profit (capital gains)

- Receiving dividend payments from your stocks

- Realizing short-term gains (selling stocks held less than a year)

- Realizing long-term gains (selling stocks held more than a year)

Non-Taxable Stock Events:

- Buying stocks (no tax at purchase)

- Holding stocks that increase in value (unrealized gains)

- Watching your portfolio grow without selling

- Stock splits or company mergers (usually)

The key concept here is “realization.” You only pay taxes when you actually realize a gain by selling the stock or receiving dividends—not just because a stock you own increases in value.

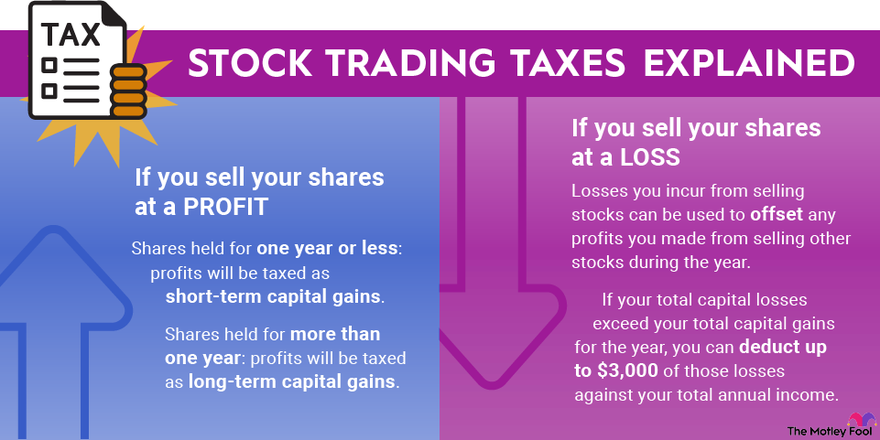

Understanding Capital Gains: The Tax You Pay When Selling Stocks

When you sell a stock for more than you paid for it, the profit is called a “capital gain” These gains are divided into two categories based on how long you held the stock

Short-Term Capital Gains

- Definition: Profits from selling stocks held for 1 year or less

- Tax Rate: Taxed at your ordinary income tax rate (could be as high as 37% for federal taxes)

- Example: If you’re in the 24% tax bracket and make $1,000 on a quick trade, you’d owe $240 in federal taxes on that gain

Long-Term Capital Gains

- Definition: Profits from selling stocks held for more than 1 year

- Tax Rate: Usually lower than ordinary income rates: 0%, 15%, or 20% depending on your income level

- Example: That same $1,000 profit might only be taxed at 15% ($150) if you held the stock long-term

This difference in tax rates creates a powerful incentive to hold investments longer! If you can extend that holding period beyond a year, you could potentially cut your tax bill significantly.

How Dividends Are Taxed

If you own dividend-paying stocks, those payments will affect your tax bill too:

Qualified Dividends

- Definition: Dividends that meet specific IRS holding period requirements

- Tax Rate: Same favorable rates as long-term capital gains (0%, 15%, or 20%)

- Requirements: Must generally hold the stock for more than 60 days during the 121-day period starting 60 days before the ex-dividend date

Nonqualified (Ordinary) Dividends

- Definition: Dividends that don’t meet the qualified dividend requirements

- Tax Rate: Taxed at your ordinary income tax rate

- Examples: Many REITs dividends, dividends from employee stock options, or dividends on stocks you’ve held for too short a period

When Do You Actually Pay These Taxes?

You don’t immediately pay taxes when you make a profitable trade or receive a dividend. Instead:

- Capital gains and dividends are reported on your annual tax return (typically filed by April 15 of the following year)

- Your brokerage will send you Form 1099-B (showing your trading activity) and Form 1099-DIV (for dividends) by mid-February

- These forms help you calculate your total taxable gains and losses

However, if you’re making substantial profits, you might need to make quarterly estimated tax payments throughout the year to avoid underpayment penalties. Generally, if you expect to owe more than $1,000 in taxes when you file your return, making estimated payments is wise.

The Net Investment Income Tax: An Extra Tax for High Earners

Some investors face an additional 3.8% tax called the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT). This applies if your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds:

- $250,000 for married filing jointly

- $200,000 for single or head of household filers

- $125,000 for married filing separately

This tax applies to investment income including capital gains, dividends, interest, and certain passive income.

Do You Pay Taxes on Losses Too?

No! In fact, investment losses can actually help reduce your tax bill through a strategy called tax-loss harvesting. Here’s how it works:

- Capital losses offset capital gains dollar-for-dollar

- If your losses exceed your gains, you can deduct up to $3,000 ($1,500 if married filing separately) against your ordinary income

- Any remaining losses can be carried forward to future tax years

For example, if you have $7,000 in capital gains but $10,000 in capital losses in a tax year, you’d pay no tax on the gains, could deduct $3,000 against your ordinary income, and could carry forward the remaining $0 to next year.

4 Strategies to Reduce Taxes on Stock Trades

While you can’t avoid taxes completely on profitable stock trades, here are some legitimate strategies that might help lower your bill:

1. Hold for the long term

The most straightforward approach is simply holding investments for more than a year to qualify for lower long-term capital gains rates. This can cut your tax rate by as much as half!

2. Use tax-advantaged accounts

Consider holding your most actively traded or dividend-heavy investments in tax-advantaged accounts:

- Traditional IRAs/401(k)s: Tax-deferred growth (pay taxes when you withdraw)

- Roth IRAs/401(k)s: Tax-free growth and withdrawals in retirement

- Health Savings Accounts (HSAs): Triple tax advantage for qualified medical expenses

3. Practice strategic tax-loss harvesting

Be strategic about realizing losses to offset gains, especially toward year-end. Just watch out for the “wash sale rule” which prevents you from claiming a loss if you buy the same or a “substantially identical” security within 30 days before or after selling at a loss.

4. Consider timing of income and deductions

If possible, consider the timing of recognizing investment gains. For example, if you expect to be in a lower tax bracket next year, it might make sense to defer selling winning positions until then.

The Importance of Good Record-Keeping

Accurate records are crucial for calculating the correct amount of tax you owe on stock trades. Keep track of:

- Purchase dates and prices (including commissions)

- Dividend reinvestments (these adjust your cost basis)

- Sale dates and prices

- Records of any wash sales

Most brokerages now report cost basis information to the IRS for stocks purchased after 2011, which makes tracking easier, but it’s still smart to maintain your own records.

Special Situations to Be Aware Of

Employee Stock Options and RSUs

If you receive stock through your employer, the tax rules are different and often more complex than regular stock investments. Usually, you’ll pay ordinary income tax when you exercise options or when RSUs vest.

Inherited Stocks

Inherited stocks typically receive a “stepped-up basis” to their value on the date of the previous owner’s death, which can significantly reduce capital gains taxes when you eventually sell.

Gifted Stocks

Gifts of stock maintain the original owner’s cost basis, plus any gift tax paid. This can create larger tax bills when you sell compared to inherited stock.

The Bottom Line: Not Every Trade is Taxable, But Profits Eventually Are

To sum things up: you don’t pay taxes merely for trading stocks, but rather on the profits you make when selling stocks and on dividends you receive. The key factors affecting how much tax you’ll pay include:

- How long you held the investment (short-term vs. long-term)

- Your tax bracket

- The type of dividends received (qualified vs. nonqualified)

- Whether losses can offset some or all of your gains

By understanding these basics and implementing some tax-smart investing strategies, you can make more informed decisions about when to buy and sell—potentially keeping more of your investment returns in your pocket rather than Uncle Sam’s.

Remember, while tax considerations are important, they shouldn’t be the only factor driving your investment decisions. A good investment that aligns with your goals and risk tolerance is usually more valuable than one chosen solely for tax reasons.

Have you found any particularly effective strategies for managing taxes on your stock trades? I’d love to hear about your experiences in the comments below!

Stock Market Taxes Explained For Beginners

FAQ

Do I pay taxes every time I sell a stock?

If you’ve owned the asset for a year or less, your gain will be taxed as ordinary income, with rates currently as high as 37%. For stocks or bonds you’ve owned for more than a year, you could face a capital gains tax as high as 20%1 on your profits (rates vary depending on your income).

Do you pay tax on every trade?

Even if the value of your stocks goes up, you won’t pay taxes until you sell the stock. Once you sell a stock that’s gone up in value and you make a profit, that’s when you’ll have to pay the capital gains tax.

How to avoid paying taxes on stock trades?

Invest in retirement accounts.

You can choose to either pay taxes when you contribute (known as a Roth account), or pay taxes when you withdraw (known as a traditional account). Whichever you choose, in the years you have your account, you can buy and sell stocks within your portfolio and not pay any capital gains tax.

What is the 7% rule in stock trading?